The Master and the Machine: Herbie Hancock’s Music and Musings

The Boch Center, Boston - October 29, 2025

Story and Photography by JD Cohen

Live music has long offered a sacred sanctuary — an escape from the mundane and, at times, brutal realities of everyday life. But we live in turbulent times, and even the transcendence of Herbie Hancock’s art at the majestic Boch Center on Wednesday, October 29, could not wholly lift the evening beyond the unsettling realities we currently inhabit.

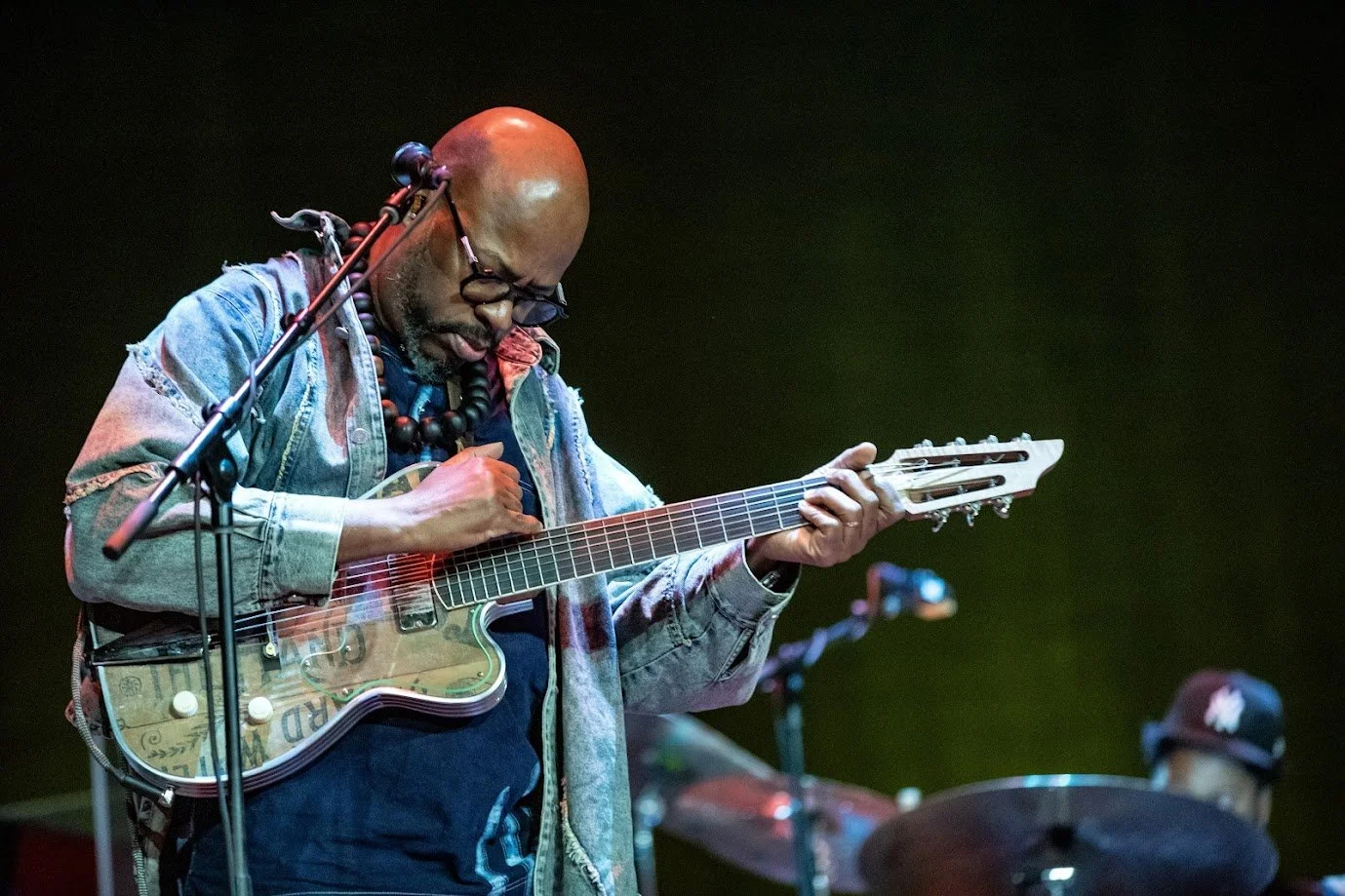

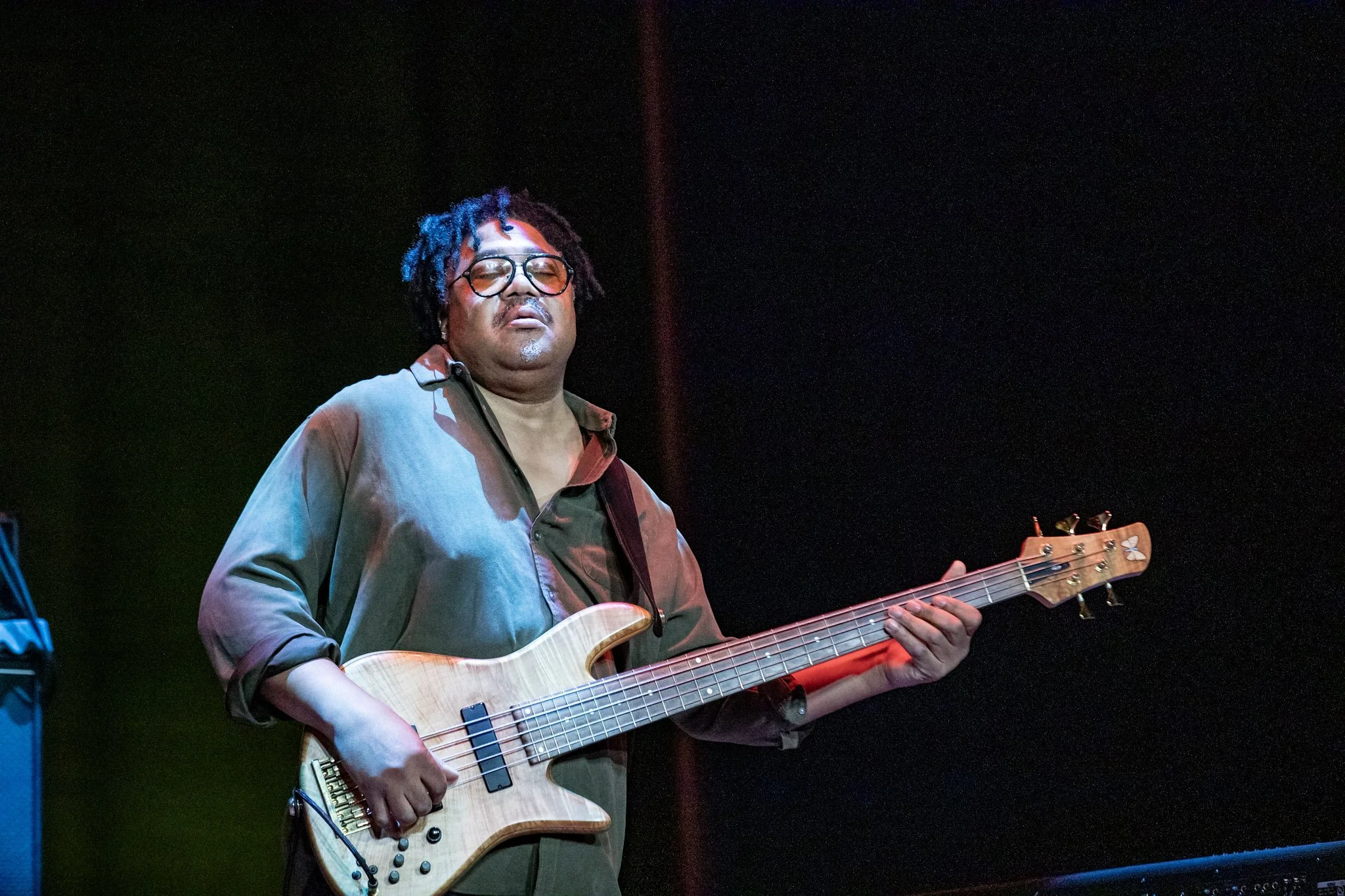

In April, Hancock — now 85 — announced his 2025 fall tour dates, a run that would take his band through the Midwest and Northeast in October and November following a summer trek through Europe. His touring band features Terence Blanchard (trumpet), James Genus (bass), Lionel Loueke (guitar, vocals), and Jaylen Petinaud (drums), all supremely talented, deeply accomplished musicians.

It’s no exaggeration to say that Herbie Hancock is one of the most influential figures in the history of jazz and popular music. Born in Chicago, he began piano lessons as a child, and at age 11 performed the first movement of a Mozart piano concerto with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra — an astonishing early milestone. After studying engineering and music at Grinnell College, he moved to New York City to pursue jazz professionally. His ascent was meteoric: encouraged by trumpeter Donald Byrd, he soon joined Byrd’s group and secured a contract with Blue Note Records at the young age of 21.

Hancock’s 1962 debut album Takin’ Off introduced “Watermelon Man,” a composition that became a hit for Mongo Santamaría and brought Hancock widespread recognition. Throughout the early ’60s he established himself both as a leader and a sideman, refining a signature sound defined by crystalline touch, harmonic depth and rhythmic sophistication and curiosity.

A defining moment came in 1963 when Miles Davis recruited Hancock for his Second Great Quintet (with Wayne Shorter, Ron Carter, and Tony Williams), one of the most celebrated ensembles in jazz history. During this period Hancock’s harmonic daring, responsiveness, and rhythmic interplay helped redefine modern jazz. Concurrently, his own Blue Note releases — including the masterpiece Maiden Voyage (1965) — cemented his status as a major composer. Pieces like “Dolphin Dance,” “Cantaloupe Island,” and “Maiden Voyage” are now foundational jazz standards.

By the late 1960s, as electric instruments and funk rhythms reshaped the musical landscape. Hancock adapted to these changes and formed a sextet that embraced electronic keyboards and avant-garde textures, culminating in Head Hunters (1973), the groundbreaking, platinum-selling album that delivered the timeless groove “Chameleon.” Subsequent albums — Thrust (1974), Man-Child (1975), and others — established him as not only a jazz titan but a boundary-breaking innovator.

Hancock continued evolving through the ’80s and ’90s, composing film scores (including the Oscar-winning music for Round Midnight), collaborating with younger artists, and integrating hip-hop and turntablism on Future Shock (1983), which featured the Grammy-winning hit “Rockit.” More than perhaps any other jazz musician of his generation, Hancock has embraced the notion that jazz is a living, evolving art form — a medium that absorbs technology, culture, and change rather than resisting them.

With all this history in mind, fans filled the Boch Center eager to see what the old master would bring to the stage: moments from the jazz canon but also the potential for something entirely new.

The program opened promisingly when Hancock and his band took the stage shortly after 8 p.m. A remarkably youthful Hancock introduced the improvised opener, “Prehistoric Predator,” explaining that it would feature ambient, prehistoric, and otherworldly textures drawn from his Korg Kronos synthesizer. What followed was exactly that — a swirling, exploratory introduction that unfolded into an extended overture and set the tone for the evening. The band’s interplay throughout the night was rich and dynamic, each member stepping into the foreground at different moments during each composition.

The sound quality at the Boch Center is always exceptional and the band's sound in theater was bright, full and well-defined. Genus’s bass sat prominently forward in the mix, anchoring the music with a muscular foundation that was at times overpowering even as Petinaud’s aggressive drumming surged with precision and power. Blanchard’s amplified, effects-soaked trumpet added a modern edge, and at times its metallic sheen lacked warmth and soul and overshadowed Hancock’s more delicate gestures. The musicianship in the band is unquestionably top-tier, but the intensity of the ensemble sometimes eclipsed the subtler textures at the heart of Hancock’s playing.

The introduction of Wayne Shorter’s classic “Footprints” offered a welcome counterbalance to some of the louder moments, with its iconic melody and Hancock’s beautiful, spacious piano work. Beginning with just piano and drums before expanding into a full-band arrangement by Blanchard, it yielded some of Hancock’s most rewarding playing of the night.

“Actual Proof” from Thrust followed, opened again with Hancock and Petinaud in tight dialogue. Their generational interplay was one of the evening’s pleasures, full of mutual respect and spontaneous reaction. Loueke, using MIDI-like effects that made his guitar resemble Hancock’s vintage electric keyboards, added another layer of sonic intrigue.

A dazzling, ten-minute version of “Butterfly” — also from Thrust — provided a final moment of pure musical immersion before the night took a surprising turn.

For the next twenty minutes, Hancock used his vocoder to deliver an extended meditation on AI, technology, and human nature. The robotic timbre of the vocoder lent Hacock’s words a futuristic gravity, but the message itself felt dissonant: a mixture of utopian optimism, moral musing, and childlike allegory. His assertion that “AI is part of our family,” and that we should raise it like a young child with proper ethics, revealed his deep commitment to innovation — but it also glossed over the increasingly fraught power dynamics surrounding AI. Behind its friendly interfaces lie vast corporate interests, opaque decision-making systems, and an uneven distribution of control. While Hancock’s intentions were heartfelt, the simplicity of his analogies — “robots don’t kill other robots,” “everyone is both good and bad” — felt naïve in the face of such complex global challenges and the uneven distribution of power related to AI developemt and its impact.

The speech was revealing, illuminating what occupies the artist’s mind, but its earnestness and lack of nuance landed awkwardly within the otherwise electric flow of the concert.

The highlight of the evening came in the closing stretch, when Hancock strapped on his white clavitar (keytar) and ran across the stage with infectious joy. The crowd reacted, getting up on their feet as he launched into a medley of his most dance-floor-ready hits — “Hang Up Your Hang Ups,” “Rockit,” “Spider,” and “Chameleon.” It was an exhilarating reminder of Hancock’s singular ability to merge virtuosity, innovation, and pure entertainment.

In the end, the concert was a portrait of Herbie Hancock exactly as he has always been: a visionary unafraid to reach, experiment, provoke, and occasionally misfire in service of pushing boundaries. At 85, he remains artistically restless — still exploring, still reinventing, still believing that music and technology can point us toward something better. Not every moment soared, but the evening was undeniably alive and unmistakably Hancock: a master still searching for the next sound, the next idea, the next possibility.

Setlist

Introduction/Overture

Footprints (Wayne Shorter cover)

Actual Proof

Butterfly

Vocoder Improv

Secret Sauce

Hang Up Your Hang Ups / Rockit / Spider

Chameleon