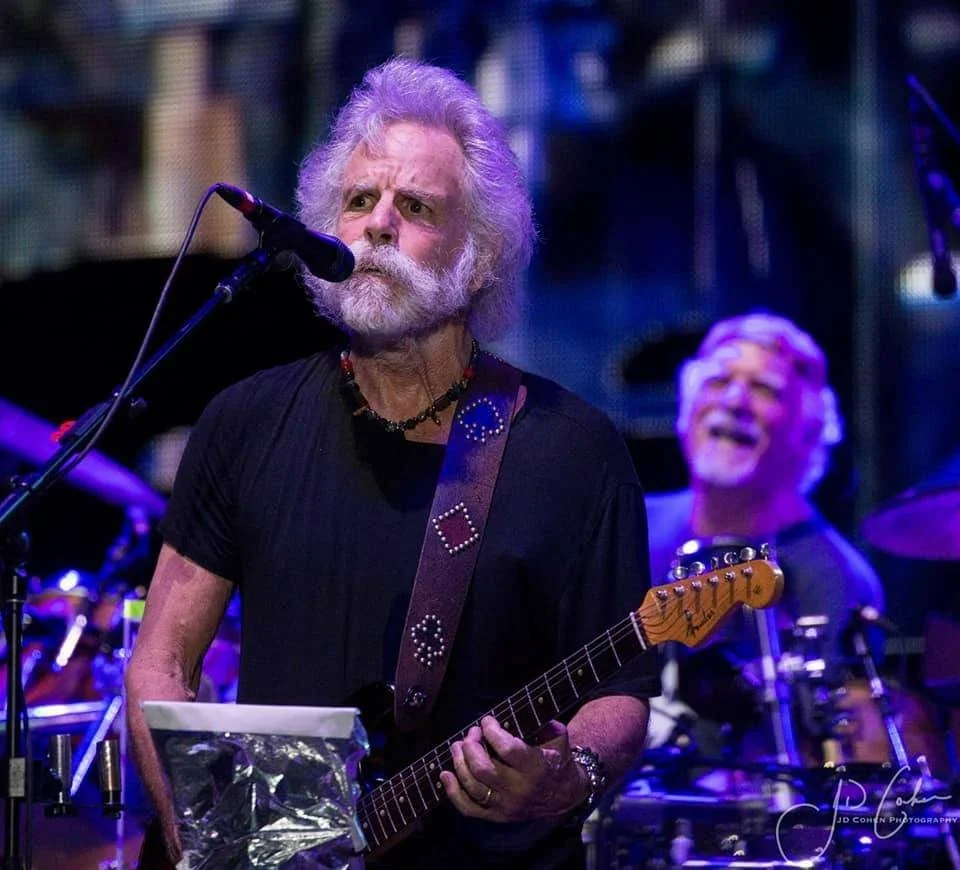

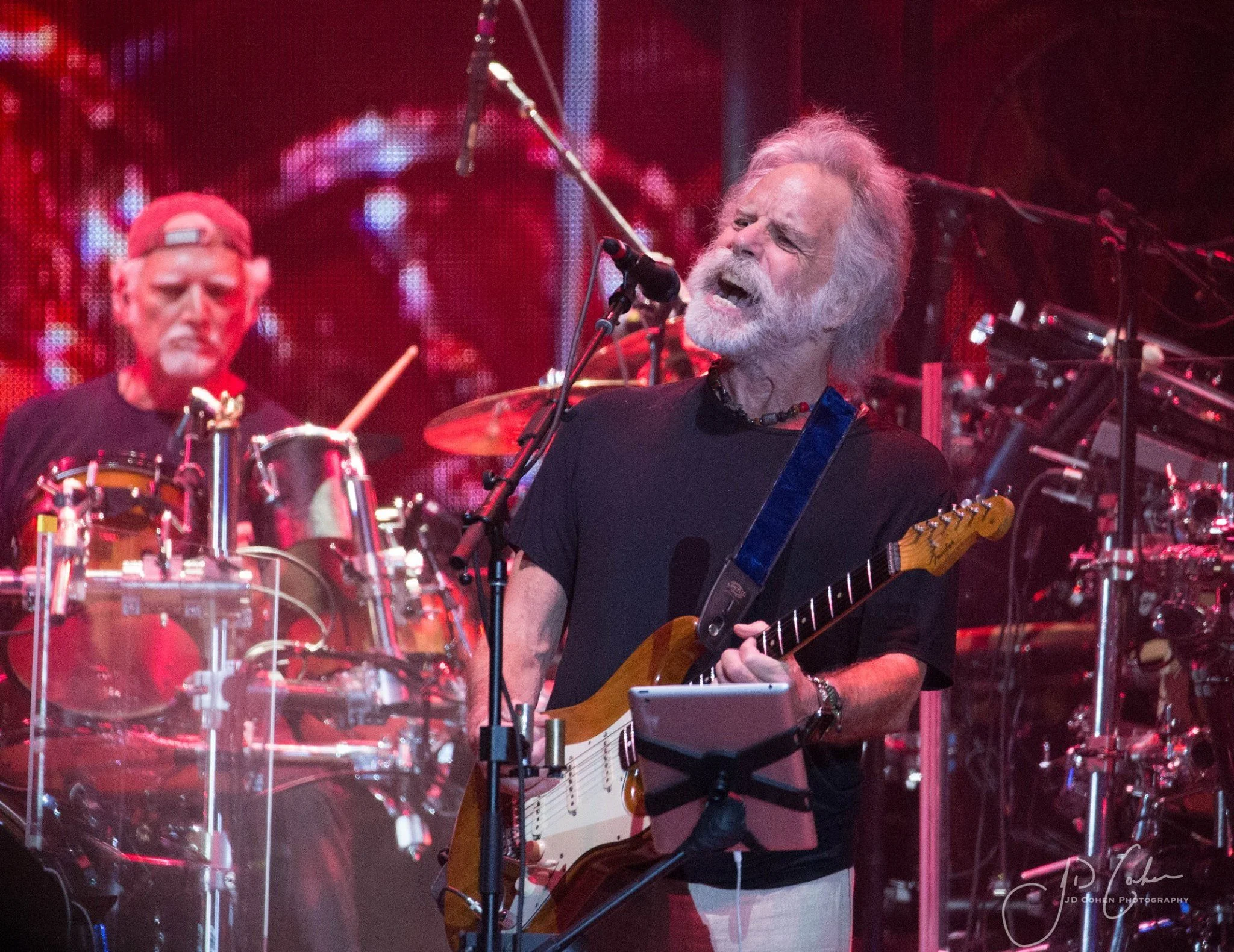

After Bob Weir: The Grateful Dead as Memory, Long Live The Grateful Dead

Story and Photography by JD Cohen

“Without Bob, the Grateful Dead wouldn’t work. He holds the whole thing together in ways most people never notice.” - Phil Lesh

The passing of Bob Weir on January 10, 2026 marks the loss of the last living link to the voice of The Grateful Dead, along with their vision and improvisational genius. The Grateful Dead is no longer a living movement but a cultural legacy to be enshrined in history.

Since their inception in 1965, The Grateful Dead proved remarkably capable of survival, continuing in new forms and configurations through the passing of its members. The music adapted, the community endured, and the idea of The Grateful Dead has remained alive as a living practice rather than a fixed memory. But now with the passing of Bob Weir something is fundamentally different. This loss brings closure to the last living embodiment of the original voice, structure, and musical philosophy of The Grateful Dead. The Grateful Dead is no more; long live The Grateful Dead.

The culture, the music, the influence, and the spirit of the Grateful Dead will continue to resonate for generations, but the original organism—the breathing, evolving entity that defined what the Grateful Dead truly was—has now passed irreversibly into history. The Death of Bob Weir is punctuated not only by the loss of a uniquely talented and beloved musician but by the end of something much greater.

Robert Hall Weir was born on October 16, 1947, in San Francisco, California, and was adopted shortly after birth by Frederic and Eleanor Weir. He was raised primarily in the Atherton and Menlo Park areas of the San Francisco Peninsula. Interviews and biographical tell of a tumultuous childhood. Weir was expelled from several schools, a fact Weir himself has documented in multiple interviews. In retrospect, Weir has suggested that he likely had what is now recognized as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Although a traditional academic environment was difficult for him, those struggles may also have contributed to his unconventional creative thinking.

By the early 1960s, Weir had become interested in the American folk revival that was active throughout Northern California. The movement emphasized acoustic instruments, traditional American song, and informal performance spaces such as coffeehouses and community gatherings. Weir’s entry into music was shaped by immersion in this folk tradition. Acoustic guitar, simple harmonic structures, and narrative songwriting defined his initial vocabulary. It was within this context that Weir met Jerry Garcia.

Weir and Garcia first met at Dana Morgan’s Music Store in Palo Alto, a known gathering place for musicians in the local folk scene. At the time, Weir was 16 years old and Garcia was 21. Garcia was already an experienced musician by the time he met Weir. Garcia was performing regularly in folk and bluegrass circles in the Palo Alto area, including appearances with local ensembles and informal jam sessions. Their relationship was largely collaborative even with the five-year age difference which corresponded to a significant difference in musical experience and technical proficiency.

Following their initial meeting, Weir and Garcia began playing together regularly. Their early collaboration focused on folk and traditional music, including blues standards, jug band material, and Appalachian folk songs. Garcia introduced Weir to a broader repertoire of traditional American music, including bluegrass, old-time, and jug band styles and it established the foundational musical relationship between them.

In 1964, Garcia and Weir became involved with Mother McCree’s Uptown Jug Champions, a jug band that included several musicians who would later form the core of the Grateful Dead. The group also featured Ron “Pigpen” McKernan, who brought strong influences from rhythm and blues and blues-based playing. Mother McCree’s repertoire consisted primarily of pre-war blues, jug band music, and folk standards.

Mother McCree’s disbanded in late 1964, and its members soon reorganized into an electric band called the Warlocks in early 1965. The transition from acoustic jug band music to amplified rock instrumentation reflected broader changes happening at the time in American popular music, particularly the growing influence of British Invasion bands and electric blues.

Weir’s role in the Warlocks was initially less clearly defined than Garcia’s. Weir was responsible for rhythm guitar and vocal harmonies. Early recordings and performance documentation from 1965 show that Weir was still very much developing his technical control and ensemble precision.

By late 1965, the Warlocks changed their name to the Grateful Dead and the rest is history. However, during the early years of the Grateful Dead, Bob Weir’s position with the band was not quite secure. Although he had been part of the group since its formation as the Warlocks, his lack of formal training and limited technical experience created tension within a band that was continuing to evolve and become more demanding musically. Garcia, in particular, was increasingly concerned with discipline, preparation, and musical coherence. As the band’s improvisations became more extended and structurally complex, Weir’s weaknesses in rhythm, timing, and harmonic awareness became more noticeable.

Multiple interviews with band members and biographers document that Weir was, at one point, close to being removed from the band. Garcia later stated that Weir’s playing was sometimes unfocused and that his commitment to musical practice did not initially match the seriousness that the band’s direction required. Phil Lesh recalled that the band briefly dismissed Weir in 1967. The separation was short-lived and informal and the episode was less a formal firing than a recognition that the group needed to reassess its internal standards and Weir needed to get more serious about his playing and his role in the band.

Weir himself has acknowledged that this period was a turning point. He has stated that Garcia confronted him directly about the need to improve his musicianship, learn theory, and take responsibility for his role in the band. In response, Weir began studying jazz harmony, chord voicings, and rhythmic structure more seriously. He has cited this moment in the history of the band as a catalyst for the development of his distinctive style, which moved away from simple strumming toward a more fragmented, syncopated, and harmonically aware approach.

Weir adapted his playing to complement Garcia’s melodic and improvisational approach and over time, he began to move away from conventional chord strumming, instead using partial chords, syncopated rhythms, and counter-rhythmic figures that interacted with the bass and drums. This style can be observed in recordings and live performances from 1966 onward.

As Weir continued to develop his unique style, his unconventional chord voicings have been immensely unappreciated and mostly unseen by the music loving public. But inside the world of the Grateful Dead, Weir’s originality and groundbreaking approach was valued as one of the key elements that differentiated the band and one of several magical elements that make the Grateful Dead so special. Jerry Garcia summed it up nicely in 1981 during interviews with authors Blair Jackson and David Gans, “he's an extraordinarily original player, in a world full of people who sound like each other," Garcia said. "I mean, really, he's really got a style that is totally unique as far as I know. I don't know anybody else who plays the guitar the way he does, with the kind of approach that he has to it." John Mayer recently said ““Playing next to Bob is like being inside a living theory of music.”

Most rock ensembles treat harmony as static and rhythm as predictable. The Dead reversed this logic. Harmony was fluid, rhythm elastic. This approach requires a guitarist who could maintain structural integrity while embracing instability. Weir became that figure. He provided a constantly shifting harmonic map that allowed the band to move freely without collapsing into chaos.

Weir’s playing was governed by a principle of harmonic suggestion rather than harmonic declaration. Instead of stating full triads or barre chords, he fragmented harmony into intervals, dyads, and incomplete voicings. This created space for other instruments to define tonal direction. In effect, he composed in real time by omission. What he did not play was often as important as what he did.

This approach aligns more closely with jazz ensemble logic than with rock tradition. In jazz, comping instruments do not state harmony overtly but imply it through rhythm, texture, and color. Weir adopted this principle instinctively, translating it into a psychedelic-rock context. His guitar became a percussive-harmonic instrument, shaping flow rather than asserting dominance. Miles Davis is famously credited with emphasizing space and minimalism in jazz, often quoted as saying, "It's not the notes you play, it's the notes you don't play". Weir’s playing is the total embodiment of this approach.

The Dead’s extended improvisations—especially in pieces like “Dark Star,” “The Other One,” and “Playing in the Band”—demonstrate Weir’s function as harmonic moderator. During moments of maximal abstraction, when tonal center dissolved and rhythmic pulse fragmented, Weir subtly reintroduced coherence through partial chords, rhythmic motifs, and harmonic anchoring. He guided the ensemble back toward form without imposing closure.

Bob Weir fundamentally redefined what rhythm guitar could be but if that wasn’t enough Weir’s songwriting voice, especially through his partnership with lyricist John Barlow, articulated a distinctly American mythic consciousness. Where Garcia and Hunter often explored inward landscapes of memory, loss, and transcendence, Weir and Barlow constructed outward-facing narratives of motion, conflict, and moral ambiguity.

Their songs are populated by archetypes: gamblers, cowboys, fugitives, wanderers, prophets. These figures are not just nostalgic but also existential. They inhabit a world where freedom is inseparable from risk and identity is constantly renegotiated. Much of Weir’s songwriting is in the tradition of American frontier literature, echoing themes in Twain, Steinbeck, and Kerouac. His songwriting was a wonderful complement to his guitar work.

Although Weir was often the most animated musician on stage, especially with the Grateful Dead, his artistic identity stands in direct opposition to the dominant mythology of the rock star guitar hero. The tradition of guitar heroism, rooted in virtuosity and spectacle, celebrates individual mastery and expressive dominance. Weir rejected this paradigm. His playing was intentionally collaborative in nature and anti-heroic.

Where the guitar hero seeks clarity, Weir embraced ambiguity and restraint. Where the guitar hero foregrounds speed and precision, Weir prioritized texture and timing. Where the guitar hero claims authority, Weir practiced humility in his playing. These qualities often made Weir’s contributions less visible but Weir mastered absence as a powerful creative force.

Jerry Garcia’s death in 1995 posed an existential challenge. The Grateful Dead had not merely lost its lead guitarist; it had lost one of its central narrative voices. For Weir, the question was not how to replace Garcia, but whether the music itself could continue as a living system rather than a relic.

RatDog became Weir’s primary vehicle for experimentation. The ensemble incorporated jazz harmony, reggae rhythm, and funk grooves into the Dead’s catalogue and improvisational language. Weir’s harmonic sensibility became increasingly sophisticated. He explored richer chord structures, deeper rhythmic syncopation, and more expansive ensemble textures.

Furthur represented another attempt to preserve continuity. The band emphasized exploratory improvisation over reproduction. Weir resisted the impulse to canonize the Grateful Dead as a museum piece. Instead, he treated its repertoire as open material, a platform for ongoing inquiry.

Teaming up with John Mayer, Dead & Company marked a cultural shift. By partnering with a younger generation of musicians, Weir recontextualized the Dead’s music for a new audience. While some critics, including this one, viewed the project as mostly nostalgic and legacy preservation, it can also be understood as pedagogical transmission. Weir assumed the role of elder architect, guiding the ensemble’s harmonic and rhythmic logic.

In Dead & Company, Weir’s guitar playing became even more abstract. He often stripped his playing to minimal gestures, allowing space to dominate. His role was no longer to propel exploration but to maintain structural memory.

The most striking development of Weir’s later career has been the Wolf Bros project. With this ensemble, he reimagined the Grateful Dead’s repertoire and his own songwriting through orchestration, jazz harmony, and chamber-music sensibility. Wolf Bros reveals Weir’s long-standing interest in American song as a living tradition. His arrangements recall the Great American Songbook, blending folk narrative with jazz instrumentation.

For many fans of the Grateful Dead, Bob Weir represented stability in a world of change. As decades passed and other members died, Weir’s presence signaled that the story was not yet finished. He was the last bridge to the original vision of the Grateful Dead as a living, improvisational organism. His guitar playing still carried the harmonic logic of the band’s earliest experiments. His voice still embodied its storytelling tradition. His philosophy still reflected its commitment to freedom, experimentation and collective creation.

With his passing, that continuity is broken. For the first time, there is no living member who participated in the Grateful Dead from its birth who can carry its original voice forward. This moment marks the transition of the Grateful Dead from a living culture to a historical legacy. The music remains, the recordings remain, the community remains, but the organism itself, the breathing entity that adapted and evolved in real time, has completed its life cycle.

The loss is deeply personal. The Grateful Dead was never just music; it was a way of understanding time and community. Many of us built friendships, families, and identities within its orbit. Weir’s passing represents the end of an era in which that culture felt directly connected to its creators. The conversation between band and audience, which had continued uninterrupted for sixty years, has now fallen silent. The Grateful Dead’s story is now whole. Weir’s death does not diminish the community; it crystallizes it. What was once fluid has become fixed. What was once evolving has become defined. This transformation carries sorrow, but also something more.

The Grateful Dead was never about permanence. It was about presence. With Bob Weir gone, presence becomes memory. But memory, when shared, becomes culture. And culture, when honored, becomes legacy.